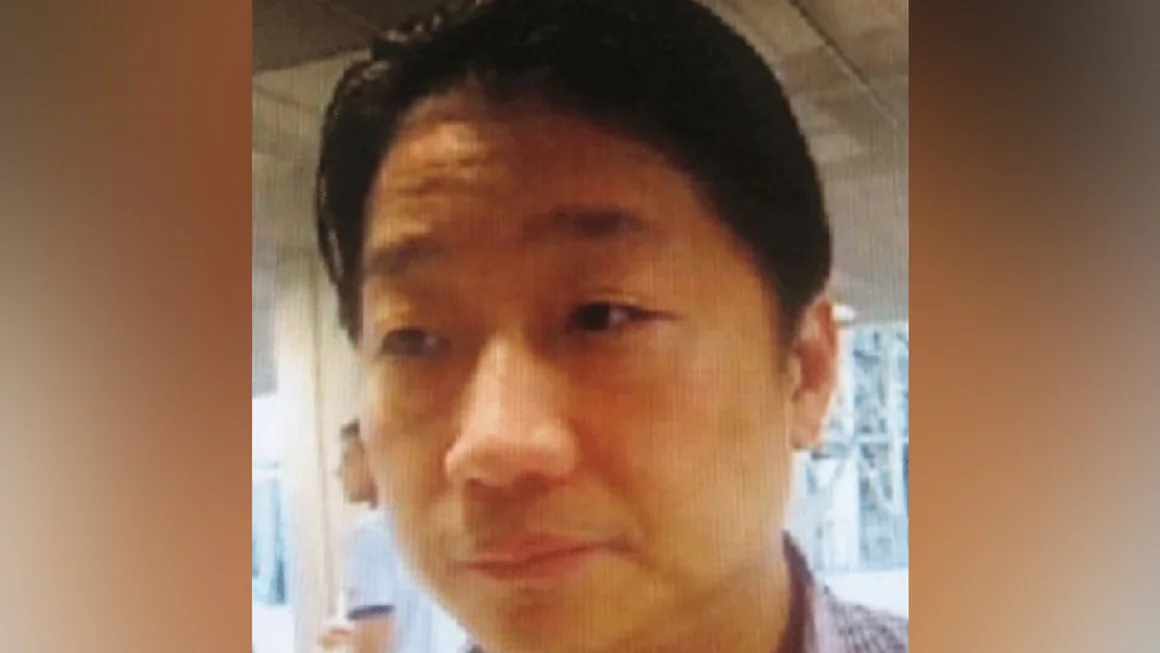

[Cover Artwork: Chris Yee]

In a maximum security prison somewhere in Melbourne, Australia, Tse Chi Lop is in and out of solitary confinement.

The 61-year-old Chinese-born Canadian national is awaiting trial for conspiracy to traffic 20 kg of methamphetamine – valued at more than $4 million – into Australia between 2012 and 2013. Tse claims he's innocent of the charge, which could land him in prison for the rest of his life, even though it represents only a tiny sliver of the illicit substances and money with which he's allegedly connected.

Tse is accused of being the mastermind behind what is likely the largest drug syndicate of the 21st Century. Its members refer to it simply as, "The Company." Law enforcement agencies came to call it "Sam Gor," which is Cantonese for Tse's nickname, Brother Number Three. In 2018, the organization is believed to have made as much as $17.7 billion – more than BlackRock's revenue or the GDP of Botswana in the same year, and 17 times what the Sinaloa Cartel made under Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman at its peak.

The Company is a uniquely modern take on organized crime, functioning less like a violent empire and more like an unencumbered tech company. It purportedly pursued efficiency and prioritized the experience of distributors like they were customers. It was simultaneously a master of logistics and a purveyor of extraordinary suffering, threading a supply chain that linked makeshift meth labs deep in the hills of Myanmar to city streets in Manila to Minneapolis.

Part of what made The Company's approach new was that it united previously warring international criminal factions to create a cohesive distribution network. This collective was able to corner markets and drive down prices, bringing in even more users. It was reportedly a major player in creating the spike in meth use which began in 2009 and has devastated nations across the world, from Bangladesh to Slovakia, South Korea to South Africa, Iran to the U.S.

As a sort of CEO, Tse wasn't what most people expect from the alleged leader of a burgeoning international drug syndicate. Where El Chapo granted interviews to Hollywood stars and is said to have personally tortured his rivals, Tse never used a phone and dressed so plainly he could have passed through most hotels without a second glance. Where Pablo Escobar owned a private zoo, hired professional cameramen to shoot his home videos and eventually entered into politics, Tse seemed to believe that anonymity yielded more power than notoriety.

Bringing Tse down required 20 drug enforcement agencies from across the globe, and the better part of a decade. But his rise is believed to have been made possible by a single, unsolved murder on a sidewalk in Vancouver.

Despite it being November, the sidewalk in front of Raymond Huang's house was almost completely free of leaves. Across the street, fallen foliage piled on the grass and spilled onto the concrete walkway, but the same space on Huang's side appeared to have been recently– and meticulously– cleared.

Like he had countless times before, Huang steered his car through his neighborhood; the area's tree-lined streets and walls of perfectly kept shrubs gave away its status as one of the richest in all of Vancouver. Part of the neighborhood's appeal was how quiet, peaceful and isolated it felt, despite being a short 10 minute drive from downtown.

Huang's house was really a mansion. 9,000 square feet, six bedrooms, 10 bathrooms, an indoor pool and a wine cellar. Huang and his wife of twenty years had called this home since it was built in 2001. Now, it was 2007 and their 10-year-old daughter, Samantha, attended a prestigious and expensive private school a few neighborhoods over. Their dogs, a German Shepherd and a Chow Chow, often roamed freely in their large yard.

Right before 11 p.m., Huang pulled up and walked to their front gate. In that short window of time, something happened – though the exact details may never be known. A 14 year old who was babysitting two blocks away said she heard what she initially thought were fireworks. A neighbor who lived down the street said she only figured out the sounds were gunshots when sirens followed shortly after. Huang's daughter, Samantha, called 9-1-1.

The police said they were unsure whether someone had trailed Huang home or had been silently, patiently waiting for him. In the weeks that followed, law enforcement slowly released details that revealed the killing had almost certainly been targeted. Not only was Huang "known" to many of Canada's police agencies, he was a "top-national-priority organized-crime target."

Sources told the local papers that Huang was a senior figure in the Big Circle Boys (BCB), a powerful and often violent Chinese organized crime group. Huang was believed to be a major player in the BCB's sale of heroin and synthetic drugs.

But that wasn't yet on the radar for most of the people living in Huang's neighborhood. When the sun came up the next morning, his body was still out front of his house – covered with a white tarp and blocking his previously pristine sidewalk.

The killer was never identified and no suspects were ever shared publicly. But what's remarkable about the murder is what happened after – for the BCB, for millions of future drug addicts, and for the next 15 years of the international drug trade. Huang's death allegedly opened up the North American drug market for Tse Chi Lop, who was fresh out of his first stint in prison, and armed with a vision for the largest drug syndicate the world has ever known.

In 2011, four years after Raymond Huang's murder, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) began working to seize drug shipments being trafficked into the country by a syndicate they didn’t yet know much about. They called the syndicate Sam Gor, after the name they’d heard used for the group’s supposed leader. They had no idea of who was actually running the show.

Australia was scrambling to respond to a dramatic surge in the usage of meth, specifically ice or crystal meth. Many places around the world were witnessing something similar. Cities across the United States reported “meth epidemics.” The UN’s Office on Drugs and Crime reported that meth-related arrests in East and Southeast Asia increased by nearly three times from 2007 to 2011. But the problem felt particularly acute in Australia. The country’s Institute on Criminology found that more than one and half million people over the age of 13 had used meth in their life – 7% of the population. Another study found a 318% increase from 2010 to 2012 in the number of times ambulances were called to crystal meth emergencies in Melbourne.

Despite their urgency, the AFP decided not to arrest all the people they caught trying to traffic drugs into the country. Instead, they tapped the distributors’ phones and monitored their movements, in hopes of uncovering the source of their product.

Meth is cheap to make and can be turned around for profits that would make even the most confident businessmen check their math. A kilo that cost $1,800 to produce in Myanmar might sell for $298,000 in Australia or $588,000 in Japan. Only one of 15 shipments needs to successfully get through for a producer to break even.

The Company leveraged meth’s cheap production costs to drop the price they offered to distributors and to offer an Amazon-like guarantee: if authorities seized a shipment of drugs, The Company would replace it, for no additional cost.

For distributors, doing business with The Company became an almost undeniable proposition. Lower prices meant even more profit, and the guarantee minimized some of the costliest risks of narco trafficking. The changes undercut competing meth producers, forcing them to stop making their own and buy from The Company. The guarantee was also what helped the AFP first identify Tse Chi Lop.

Over the course of a year of the AFP’s surveillance of distributors, a cycle emerged: after a shipment was seized, distributors would bounce back with another at surprisingly quick rates. Distributors were taking The Company up on their guarantee, only to have it intercepted again. And again. And again. After taking loss after loss, The Company demanded answers, noting that shipments to other parts of Australia were getting in mostly without problem.

Through their wiretaps, the AFP learned that syndicate leaders had called for a face-to-face meeting with distributors. It was a potential breakthrough for the AFP, a chance to put a face to the man they'd only heard referred to as Brother Number Three.

The meeting took place in Phuket, Thailand, a place becoming known the world over for being deluged each year by tourists in pursuit of choose-your-own adventure style vacations. On one side of the island, white sand beaches back up to thick jungles. A short drive away Bangla Road, a crowded pedestrian street with bars and clubs, comes to life each night with bright signs and a steady back and forth of tourist money in exchange for quickly made drinks. On the other side of the city, Old Town Phuket is lined with short, brightly-colored buildings, mostly built in the 1900’s for immigrants, most of them Chinese, seeking to cash in on the area’s thriving tin mining industry. In 2012, more people would visit Phuket than would pour into Las Vegas, Prague and Mecca, respectively.

Amongst the many visitors to Phuket that year were members of The Company, who reserved most of a resort for their meeting. As AFP lead investigator Roland Singor recalled, 20 to 30 people gathered around the pool. Many of them were large, imposing bodyguards who Singor would later learn were trained kickboxers, ensuring protection for Tse even when passing through customs without guns.

The Australian distributors entered into the pool area and sat across the table from a man wearing loafers and a polo shirt, making him look more like a corporate middle-manager on a Friday than a supposed drug kingpin.

Despite appearances, Singor said, “There was no doubt that he held the room at that table. He was in charge and he was, you know, a man of authority.”

For the first time, the AFP could connect a nickname to a face and, in turn, to an identity. Sam Gor, or Brother Number Three, was Tse Chi Lop.

Singor described this revelation as a watershed moment in an investigation that would play out for the next decade. But halfway around the world, the FBI was already quite familiar with the name Tse Chi Lop.

In 1992, New York City was being flooded with heroin that was cheap and dangerously pure, much of it from South-East Asia. FBI Special Agent Mark Calnan followed a tip to a street corner in the Bronx, where he arrested a street dealer. Calnan came to learn that the dealer's supplier was Yong Bing Gong, a man known as "Sonny” who was running a trafficking business from jail, where he was serving a life sentence.

What started as a routine drug bust quickly evolved into a complex international Operation named “Sunblock” – a portmanteau of “Sonny” and the cellblock where he lived. One arrest and seized shipment at a time, investigators worked to untangle an intricate web of illegal activities that stretched continents. Almost every incident led back to the name Tse Chi Lop, a shadowy figure who clearly played a key role in the operation.

Born in Guangzhou during China's Cultural Revolution in 1963, Tse had witnessed his country's transformation from Mao’s rigid communist ideology to Deng Xiaoping's capitalist reforms and new mantra: "to get rich is glorious." In the years that followed Mao’s downfall, many former Red Guard members – young people, many of them students, who had taken up Mao’s call to action by forming paramilitary groups – fled to Hong Kong. There, some of them channeled their military experience and hardened solidarity into forming a crime triad called the Big Circle Boys (BCB), a reference to the red circle that was commonly around the city of Guangzhou on maps. Somewhere in this time of transition, Tse had made his way to Hong Kong and joined the BCB.

By 1988, he had advanced enough through the triad to move to Toronto, one of the places the BCB had expanded its criminal operations. In Canada, the group was involved in car theft, prostitution and, at one point, had made almost all of the counterfeit credit cards in the country. It was also finding success by importing massive amounts of heroin and often trafficking it into the United States.

Tse kept up a domestic facade, marrying Tse Yim Fun in 1989 and having two children by 1990. He worked legitimate jobs at Fujifilm and Kodak. But behind this conventional exterior, he was making a name for himself by helping to orchestrate direct negotiations between the Big Circle Boys and a Montreal-based Mafia group, the Rizzuto crime family.

"At the time, Italian mobsters normally wouldn't have anything to do with the Asian gangsters," said Larry Tronstad, a former Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) staff sergeant who supervised the anti-Mafia unit in Toronto.

By 1995, Operation Sunblock had methodically worked to identify traffickers on both sides of the US-Canadian border, from Paul Kwok in Ontario who moved heroin between countries, to "Manny the Barber" on Long Island, who would facilitate its transport in the United States. Sunblock had gathered enough information to indict or arrest more than a dozen people, including an indictment for “Sonny” Yong Bing Gong in prison.

But just as the operation seemed to get closer to Tse, he had fled to mainland China – an untouchable sanctuary where Western law enforcement had no power at all. Years of meticulous investigation ended with Tse out of their reach.

"He could have been on Mars as far as I was concerned, because we had no extradition treaty with China and no cooperation with the Chinese," said Agent Calnan.

The FBI and the RCMP had all but given up on catching him when an informant told Canadian officer Mario Lamothe that Tse would be in Hong Kong. Despite returning to Chinese control in 1997, Hong Kong had maintained extradition cooperation with the United States. Calnan and Lamothe, sensing Tse’s first big mistake, scrambled to book flights.

On August 8, 1998, Hong Kong police swooped in to arrest Tse, after he walked into a restaurant in the neighborhood of Tsim Sha Tsui. Calnan and Lamothe watched the culmination of their years-long pursuit.

“I was blown away by how normal he was, how he could blend into a crowd,” said Calnan, who met with Tse after the arrest to tell him he’d be extradited to the United States. “It was nothing about him that shouted out, you know, international drug trafficker.”

Two years later, Tse would be sent to Federal Correctional Institute in Elkton, Ohio, having pled guilty to a single charge of conspiracy to import heroin into the U.S. and sentenced to nine years in prison.

“It was the highlight of my career,” said Calnan. “But I didn’t think about Tse Chi Lop a single moment after that.”

Outside the prison that now held Tse, the international drug trade started to shift. Synthetic drugs were on the rise and offered higher profits with fewer supply vulnerabilities. The change would’ve been very clear to Tse and to Lee Chung Chak, a British-Chinese citizen with his own history of drug trafficking who was imprisoned at Elkton at the same time.

When Tse was up for early release, he told the courts he had “great sorrow” for his crime and that, upon release, he would open a restaurant. But shortly after he walked free in 2006, the U.S. lost track of his whereabouts. Having formed a powerful partnership with Lee that would last for the next 15 years, Tse returned to Asia and started making moves to create The Company.

The Company was made up of five separate Asian crime groups, also known as “triads,” including 14K Triad, Wo Shing Wo, Sun Yee On, Big Circle Boys and Bamboo Union. The triads united to grow the international market for drugs, which required putting aside their differences and consolidating their connections with the Yakuza in Japan, biker gangs in Australia, the ‘Ndrangheta and the Camorra of the mafia and other organized crime groups from Asia, Africa and Europe. The groups seemed to have realized – or someone had convinced them – that competitors fight over market share, but partners can exponentially grow the market itself.

Though Tse and The Company remained hidden, their cohesiveness created an operation that was believed to have unimaginable breadth and scale. Warehouses in the mountainous, secluded Wa State in Myanmar transformed row after row of chemicals stored in 50-gallon drums into record amounts of meth. Many also produced heroin, ketamine, MDMA and yaba, a cheaper form of meth laced with caffeine.

People serving as drug mules, or sometimes lab workers reeking of the chemicals used to make meth, brought the finished products down from the hills. Boats left ports, packed tightly with tonnes of illicit substances. The amount of methamphetamines seized in East and South-East Asia increased eightfold between 2009 and 2018. Countries such as India, Australia and the Philippines seized shipments of vacuum-sealed tea-packets of meth, one of The Company’s signature ways of transporting drugs.

As profits rose, so did the devastation on the other end of the supply chain. Chinese authorities reported in 2014 that meth-related violent crime in just nine months exceeded the total of the previous five years combined. In the Philippines in 2018, more than 88 percent of hospital admissions related to drug abuse were due to meth usage. More than 206,000 people across Southeast Asia sought treatment for methamphetamine addiction in 2020, a figure experts believe represents only a fraction of those affected. As places were flooded with meth, drug prices plummeted while purity remained high, a deadly combination that simultaneously increased affordability and harm.

No one seems to have benefited more from this perfectly constructed supply chain of misery than Tse himself. He continued to evade authorities, but his life morphed into one of extreme luxury. He flew his entourage around Asia, hosting lavish parties and staying at the finest resorts. He was a regular at casinos which allegedly served the dual purpose of helping to launder millions of dollars and providing an outlet for his intense gambling habit. He reportedly lost $10 million at the Sands casino in Singapore, and left without paying. In Macau, investigators say he lost $66 million in one night.

In the ten years since his release, Brother Number Three had built a sprawling empire and amassed unimaginable fortunes, all while remaining in the shadows. But that was all about to change.

In November 2016, a young man named Cai Jeng Ze arrived at the Yangon International Airport in Myanmar to catch a flight bound for Taiwan. Police stopped him, noting his nervous demeanor and blistered hands.

A search revealed two packets taped to Cai’s thighs, each containing 80 grams of ketamine. However, the most valuable discovery wasn’t what was strapped to his body, but what was on the two phones he was carrying: information about never-before-seen parts of the Company that provided clues and evidence on how to bring it down.

Myanmar police said the phones had a video of a man being gruesomely tortured with a blowtorch and a cattle prod. The man claimed to have hastily thrown 300 kg of meth from a boat out of fear of being detected by law enforcement.

Police also said they found thousands of messages and call logs about meth deals, which revealed the scale of Sam Gor’s operations in Myanmar and their sea-based smuggling routes to Australia. Photos on the phone were later verified to be images of past drug shipments intercepted in China, Japan and New Zealand. In all the incriminating information, investigators found a photo of Tse Chi Lop himself. Investigators who had spent years desperately chasing the man atop The Company finally had a break.

The hunt for Tse Chi Lop required a combination of tiny, incremental discoveries and historically large drug busts.

In the middle of 2017, a $300,000 boat called the Valkoista successfully brought hundreds of kilograms of methamphetamine through the port of Geraldton in Western Australia. While the boat had been paid for by someone else, it was listed under the name Joshua Joseph Smith, a man who had been recruited that month for a mysterious "job out west." In response to the massive shipment, Australian authorities began monitoring Smith's crew, including when they met with alleged Sam Gor syndicate members in Bangkok a month later.

According to prosecution claims and court testimony, the shipment was planned as the first of two deliveries. The second shipment was set for the end of the year and would be significantly larger than the first, a leap from hundreds of kilograms of meth to 1.2 tonnes. After months of watching and listening, Australian authorities intercepted the second shipment at the same port of Geraldton. According to AFP documents, it was Australia's largest-ever methamphetamine seizure at that time, valued at approximately $1 billion.

The march towards the top of The Company inched even closer in 2019, when Reuters published an exposé on Tse Chi Lop. A two-year investigation by journalist Tom Allard, the article was the first public revelation of an Australian-led multinational investigation involving about 20 agencies from across Asia, North America, and Europe. According to the report, Reuters journalists reviewed "a document containing AFP profiles of the Operation's top 19 syndicate targets" which identified Tse Chi Lop as the leader of the Sam Gor syndicate, and more sinisterly, as "Target 1."

The alleged leader who spent years operating in the shadows now had his name and face in the international media. Throughout Asia-Pacific, Tse's associates began to distance themselves from their newly visible leader. The empire began to fragment.

As the subject of a major multinational investigation and with the AFP issuing a notice with Interpol for his arrest, Tse looked for hiding spots. One of the last places Tse had connections to protect him was Taiwan, both because of his connections with local law enforcement, but once again because of extradition treaties. Both China and Australia had issued arrest warrants for Tse, but neither had extradition agreements with the self-governing territory.

Tse spent most of 2020 in a wealthy area of Taipei, protected by bodyguards. Taiwan's stringent COVID-19 measures made it difficult for him to leave, but also provided a legitimate reason for staying in the country, allowing him to extend his visitor status under special circumstances.

Despite the apparent protection, the National Police Agency in Taiwan "obtained a court order to put Tse under surveillance." At the beginning of 2021, Taiwanese authorities denied his application to extend his stay. Not only was Tse forced to leave, the Taiwanese government notified Dutch and Australian officials of Tse's impending flights back to Canada. Tse's lawyer would claim the Taiwanese government deliberately – and "against his will" – put him on a flight with a stopover in the Netherlands instead of the nonstop flight to Canada that left an hour earlier, a change that was "legally more favorable for Australia."

On January 22, 2021, Dutch National Police waited at Amsterdam's Schiphol Airport for an EVA Air flight from Taipei to touch down. Tse – a decade after the poolside meeting in Phuket, half a world away from the superlabs in Myanmar – stepped off the plane and was arrested.

Tse Chi Lop appeared in Melbourne's Magistrates' Court on a December morning in 2022. Court officers remarked that his case was "bigger than Ben-Hur," yet the man himself, now silver-haired, bespectacled, dressed in gray tracksuit pants and a black collared shirt, seemed as ordinary as ever.

Tse's arrest should have represented a serious rupture to the drug trade of Australasia, and authorities celebrated it as such. Yet, the data about meth trafficking suggests otherwise. A record 190 tons of methamphetamine was seized in East and Southeast Asia in 2023 – the highest amount ever recorded for the region. Street prices are dropping – the clearest market indicator that supply had not been meaningfully disrupted.

If anything, the drug market has diversified. Beyond meth, the region seized "a record 27.4 tons of ketamine in 2022, an increase of 167 per cent," with "large mixed shipments of methamphetamine and ketamine" indicating that "organized crime continues to push the two drugs as a package to grow ketamine demand."

Almost like a corporation that has long since transcended depending on any single executive, the towering, lucrative drug enterprise that Tse Chi Lop is accused of constructing carries on without him – perhaps the greatest indication of his success.

The Company that Tse is accused of creating wasn't just designed to make a fortune. It was designed to go on seamlessly without him.